Ken Dryden and the Cambridge University Ice Hockey club

Introduction

This story is written as a tribute to Ken Dryden, in recognition of the time he spent with us and the impact he made, both in the moment and in the years that followed.

We have worked hard to tell this story as it happened. We are fortunate to have firsthand accounts from those who were there, along with archival records and newspaper articles.

Although these events happened long ago, they remain vivid in our minds, as if they happened yesterday.

Glenn Blaylock

2025

Foreword

At one of the world’s oldest universities, steeped in tradition and ceremony, a group of students took to the ice without fanfare, without proper preparation, and often without proper gear. They had no rink to train on, no time to revive long‑dormant skills, and no illusions about the seasoned, physical opponents they would face.

They encountered challenges that might now seem insurmountable, but they met them with persistence and ingenuity. Once on the fringe of university life, they found themselves thrust into the forefront - visible, supported, and celebrated.

Remarkably, Ken Dryden, one of the greatest goaltenders in ice hockey history, became part of the story. He shared his time, his wisdom, and his presence, leaving a lasting impact on those who felt privileged to meet him.

Soon after these events, Cambridge ice hockey teams would finally gain access to a rink. They would practise, hone their skills, and build their fitness.

This story is about what came before - when heart, humour, and heritage were enough.

A Legend

Ken Dryden standing 6 feet 4 inches tall seemed to fill the net. He ended his extraordinary career on May 21, 1979, backstopping the Montreal Canadiens to a 4–1 win over the New York Rangers to secure the Canadiens’ fourth straight Stanley Cup. He retired that very night, never to play another professional game. At just 31 years old, he walked away at the peak of his career.

Across seven full seasons and nearly 400 games, he lost only 57 times and recorded 46 shutouts—a ratio that still stands unmatched. During his years in Montreal, he captured six Stanley Cup championships, a Conn Smythe Trophy as playoff MVP, a Calder Trophy as rookie of the year, and five Vezina Trophies for allowing the fewest goals.

His legacy extended well beyond the NHL. Cornell University retired his number in honour of the champion who led the team to the 1967 national title. He also represented Team Canada in the hard-fought 1972 Summit Series against the Soviet Union.

Amid all this, he completed a law degree at McGill University and articled with a Montreal law firm. In the fall of 1980, he moved with his family to Cambridge, England to write about his storied hockey career.

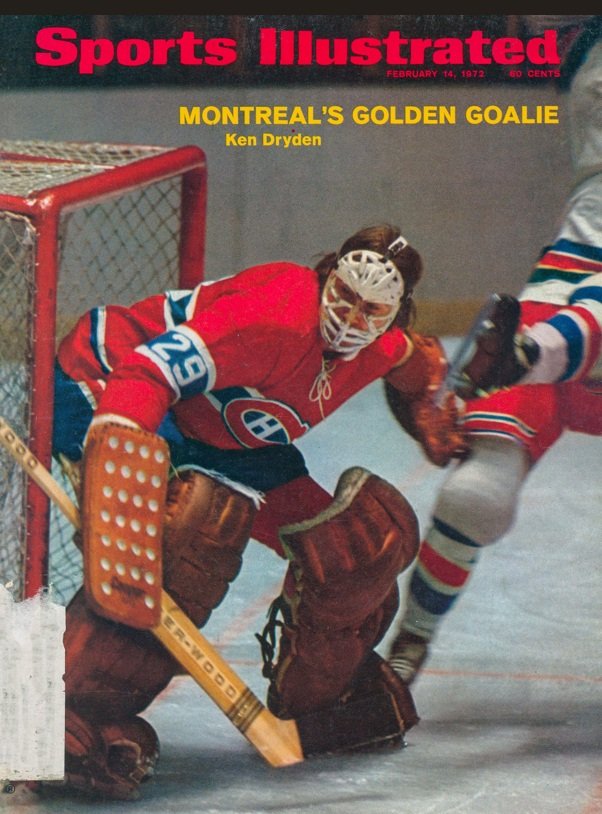

Ken Dryden, 1972, Sports Illustrated

P. McConville/Alamy

Prologue

It was February 2018 in St. Moritz, Switzerland. Warm light spilled across the banquet hall, as students and alumni gathered, most in tuxedos, others in blazers and ties.

They came from Europe, Canada, the U.S. and from distant parts of Asia and elsewhere around the world. Drawn together by a shared legacy, they were there to celebrate a milestone, the 100th varsity match between the Oxford and Cambridge Ice Hockey Clubs.

At the front of the hall, Michael Talbot stood behind a polished lectern. His deep passion for the varsity rivalry was rooted in years of experience—he had played for Oxford, coached the team, and published research on its history. With a voice steady and rich with reverence, he traced the storied relationship between the two clubs, beginning with their first match in 1885 on an outdoor rink in St. Moritz.

Ceremonial Ice Hockey Puck

With a final glance at his notes, Michael looked up and smiled. “As I compile the history of this remarkable tradition,” he said, “I welcome any stories you may have, especially those that capture the spirit behind the data.”

The room stirred with quiet conversation and clinking glasses as Michael stepped back. From opposite ends of the hall, two figures began to make their way toward him. One was a man in his early thirties, his stride confident, eyes bright with purpose. The other, older by three decades, moved with a calm deliberation, his expression unreadable but attentive.

They arrived at the front nearly in unison. The younger man extended his hand and introduced himself.

“Michael,” he said, “my name’s Cal Nicholson. I’ve got a story to tell, and it’s hard to believe unless you were there.

It was November 2011, I was in London, and it was a typically cold, miserable, drizzling morning. I was on my way to a workshop where academics and policy bureaucrats were gathering to talk about ‘climate migration’.

When I arrived, I scanned the list of attendees and recognised several of the academics. And then I saw one familiar name that made me do a double take: Ken Dryden. His official role was a kind of ambassador with the Canadian government.

It couldn’t be that Ken Dryden, I thought.

I entered the room.

And there, unmistakably, he was. Despite sitting alone in the back row, trying to be unobtrusive, he loomed. Among the slight academics in the room, the scene looked like a Far Side comic.

I casually wandered to the back row and sat next to him. After a few minutes of rather serious conversation about climate, I asked, ‘By the way, have you ever considered playing goalie in hockey?’

He raised his eyebrows and broke into a grin. ‘As a matter of fact, I have.’

We both laughed, and I mentioned that I’d played goalie too.

He asked where I had played. ‘Cambridge University,’ I replied.

‘Oh really? As it so happens, I coached them back in the early 1980s. I was in Cambridge, working on my book one day, when someone knocked on my door and asked me to join the team. Turns out he was the captain. Rather than play, I offered to coach their goalie.’

I could hardly believe what I was hearing. After all, who would have the audacity to invite Ken Dryden, one of the greatest goalkeepers of all time, to play for a university team?”

The older gentleman, who had been listening intently to Cal’s story, laughed. Cal and Michael turned to him.

“That was me,” he said.

Year 1980 - Priorities

It was September 1980, and I was peering out the window of the Boeing 747 while it circled above the clouds waiting for its turn to descend and land at Heathrow airport.

I was returning to Cambridge for my last year.

Margaret Thatcher had been elected Prime Minister of the U.K., and the ripple effects were immediate. The British pound surged in value, and tuition fees for international students climbed sharply. For me, it meant leaving a comfortable government research job in Vancouver as it did not pay enough to cover the increased costs. If I wanted to study in the U.K., something had to give. I packed my things, traded comfort for risk, and set off for the mountains.

I spent the summer working on a hydraulic rock drill, hefting twelve-foot steel rods while balancing on a narrow boom, feeding them into holes we drilled into solid granite. When the drill had pushed deep enough, we packed the holes with dynamite, set the charge, and stepped back as the wall of rock exploded.

As the plane circled, I went over the notes I had prepared, outlining my key priorities for the academic year. Top of the list was: build a competitive ice hockey team.

I still found myself musing on the use of the word ‘ice’ to describe hockey in the U.K., where ‘hockey’ typically refers to a sport played on grass, using short sticks and a hard plastic ball.

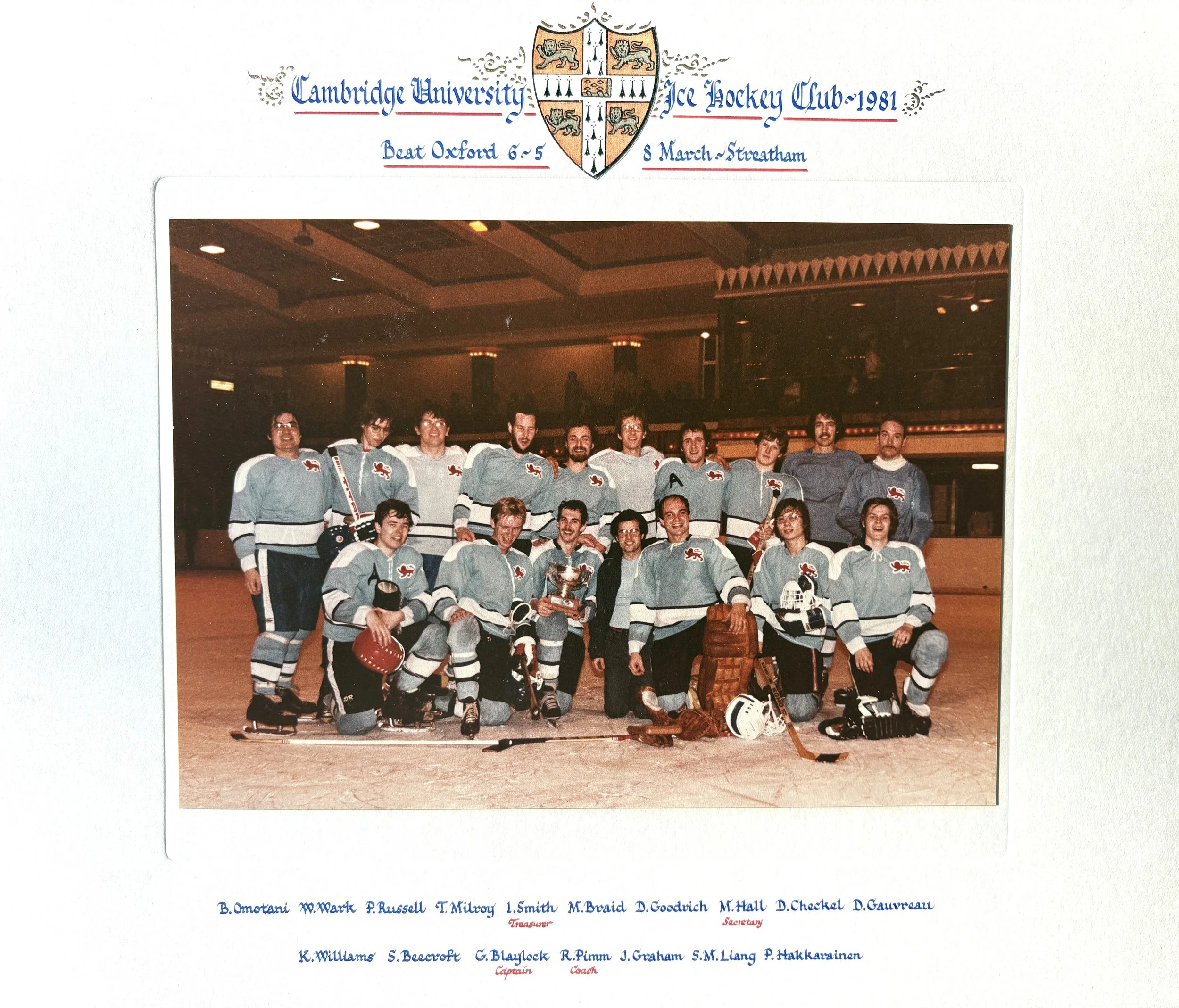

I thought back to the team lunch held at King’s College in April, the last time the Cambridge Ice Hockey Club was together. Spirits were high, and we were still savouring our recent win over Oxford.

It was a gorgeous spring day. The skies were clear, and sunlight streamed through the tall windows lining the room.

Bernie Funston, the team captain, stood to get everyone’s attention.

“It’s time for us to choose who will captain the team next season,” he said.

He handed out slips of paper and asked each of us to write down the name of the person we felt would best lead the team, then place it in the bowl at the center of the table.

Once everyone had voted, Bernie reviewed the names. He smiled and announced, “I’m very pleased to hand over the responsibility of leading the club forward to Glenn.”

The room erupted in cheers, clapping, and words of encouragement.

After the team picture was taken, I walked home with Elaine, who had been my guest to lunch. She said, “Congratulations. Being selected as Captain is quite the honour”.

I wanted to sound more enthusiastic, but I explained:

“The cheers and jubilance from the team were less about congratulating me and more about relief that they hadn’t been chosen. Everyone knew the role could be daunting as the hockey club was run entirely by the players, with no infrastructure to lean on. The captain was not just a leader on the ice; he was the General Manager, Coach, Equipment Manager, player, and problem-solver rolled into one.”

The new academic year was about to begin, and it was time to start shaping the next chapter of the varsity team. Our netminder from last season had graduated and replacing him would not be easy. Experienced ice hockey players are rare enough in England, but someone with real experience in goal? That is a whole different challenge.

There are many names for the player who defends the goal, including Netminder and Goalkeeper. In ice hockey, they are most often called simply, the Goalie.

Our plane started descending and a most remarkable year was about to unfold.

Searching for Talent

Finding students who played ice hockey was no easy task. There was no internet, no social media, no cell phones or websites. If we wanted to build a team, we had to be inventive by finding ways to spread the word that Cambridge had an ice hockey club.

Ian Smith and Martin Hall volunteered to serve as treasurer and secretary, as well as to assist with other team duties.

We set up a table at the Freshers’ Fair, the annual student event where clubs, societies, and teams introduced themselves to the incoming students. Held in the upstairs room of the Guildhall beside Market Square, the fair was a lively mix of possibility and tradition. Tables lined the room, each representing a different corner of university life, from the Chess Club and the Gilbert and Sullivan Society to the Fencing Club and Musical Theatre.

Our table stood quietly among them, marked by a hand-lettered sign pinned to the wall: Cambridge University Ice Hockey Club. On the table, we placed a pair of ice skates, a hockey stick, a few pucks, and a poster from the previous varsity match. Students would walk by, pause, and glance over with an inquisitive look; curious, perhaps, that such a sport had found its way into the heart of Cambridge.

“Is there really an ice hockey team in Cambridge?” they would often ask, eyebrows raised in disbelief.

“Yes,” we would reply, “there’s a long history of the sport at the university.”

The next question was almost always the same: “Is there an ice rink in Cambridge?”

“No,” we would admit with a smile.

That answer usually earned a puzzled look, followed by a polite nod as they drifted toward the next booth.

But every so often, a student, from Canada, Europe or the United States, would linger, intrigued. Curious to learn more, they would ask questions, and we would invite them to the team meeting scheduled soon after the fair.

Another way we found prospective players was through word of mouth. Returning teammates would visit the colleges, asking if there were any students from countries where ice hockey was more than just a curiosity.

That is how I had been recruited.

Not long after I arrived in Cambridge for my first year, I was opening the door to my room in residence when a student came up to me.

“Are you Glenn?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“I’m David Camp,” he said, then quickly added, “Do you play ice hockey?”

I was taken aback. It seemed like a peculiar question. “I played as a kid,” I said, “but stopped when I was fourteen.”

“Fantastic!” he said. “You’ll be on the team.”

“What team?” I asked.

“The Cambridge University Ice Hockey Team,” he answered, handing me a slip of paper with the details of an upcoming meeting. “Be sure to attend,” he added, then hurried away.

I stood there, trying to process what had just happened. I had not played hockey in years. Yet here I was, holding a slip of paper - an invitation to join a team I hadn’t known existed, in a place I never imagined lacing up skates again.

Welcoming New Players

We posted notices throughout the colleges and university buildings, announcing that the university had an ice hockey team and inviting students to attend the first meeting in the Erasmus Room at Queens’ College.

With the meeting moments away, I was keen to see who would arrive and what kind of experience they’d bring to the team. The students wandered in. Some had been on the team before and were eager to reconnect with returning players. Others arrived with a look of anticipation, unsure of what to expect.

I approached those I had not met before, welcomed them to the club, and asked about their hockey background. A few shared that they’d played recently. Meeting Steve Beecroft from Canada was a highlight, as he had represented his town on its all-star team.

Several others admitted they had limited experience.

Sean-Mun Liang, a first-year undergraduate from Montreal, told me he’d played one season when he was thirteen. He loved the sport, but in fifteen games, he scored just once. “I’d been given Howie Meeker’s book Hockey Basics, which preached ‘pass, pass, pass,’ so I never took a single shot on net. My only goal came off a pass from behind the net, it hit someone, took a lucky bounce, and somehow went in!”

We both laughed. I said, “Well, Sean-Mun, that’s about to change. We’ll be counting on you to take plenty of shots on goal this season.”

“Welcome,” I said, drawing everyone’s attention. “I’m so glad you’re here tonight to learn more about the Cambridge University Ice Hockey Club. Joining this team offers a unique opportunity to build friendships and create some of the most memorable and meaningful experiences of your time in Cambridge.”

I continued, “We have a wide range of skills and experience, and everyone will have the opportunity to play during the first part of the season. Team selection won’t happen until the new year.”

One player half raised his hand and asked,

“I haven’t been on skates in years. Where and when do we practise?”

“We don’t practise on ice as there’s no rink in Cambridge or nearby.” I clarified.

The new players looked confused and concerned. The returning players just smiled.

“Do the other university teams we play have rinks?”

“Other than Oxford, we don’t play university teams. We compete in the British Ice Hockey League; teams from cities across England, many of which import players from Canada and Europe.”

He looked even more uneasy.

“What equipment do we use?” he asked.

“We have an assortment handed down over the years,” I explained. “You will get a chance to rummage through it and find padding that fits.”

“What about skates and sticks?”

“The skates we have are not great, so you might want to have yours shipped from home,” I said. “We’re fine for sticks. When I was in Canada this summer, my sister’s wholesale sporting goods company donated two dozen, and we have enough face masks for everyone thanks to Bill Scott, a member of last season’s team.”

He paused, thoughtful.

“So let me get this straight. We play teams with imports, we don’t practise, and we wear equipment that sounds dubious at best. Yet you’ve said being part of this team will be a highlight of our time in Cambridge.”

“That sums it up quite well,” I said.

He grinned.

“Well, it sounds so absurd I could not possibly miss it. Count me in.”

The veteran players laughed, while the new students offered uncertain smiles, still trying to make sense of it all.

I then asked if anyone had experience playing goal.

Jeff Graham, a graduate student new to the university, called out, “I played goal in one game for an intramural team at McGill University.” He said it with a hint of jest, expecting a laugh.

But I wasn’t laughing. I was looking at him intently.

Jeff hesitated, then added, “But I’m not a goalie.”

Even as he said it, he had a nagging feeling that maybe he should not have mentioned it at all.

Dryden’s in Town

With our first game fast approaching, we still did not have a goalie. We were set to face Nottingham Panthers; a team stacked with imports from Canada and Europe. The looming embarrassment was hard to ignore, and it was beginning to interfere with my studies. Every time I tried to focus, my mind drifted to the empty net.

One evening, I was climbing the grand staircase at Darwin College, surrounded by a crowd heading to the dining hall. The hum of conversation echoed off the stone walls. Then, from behind me, I heard Brian Omotani call out:

“Hey Glenn! I hear your goalie problems are solved!”

I turned, puzzled. “Not that I’m aware,” I replied.

Raising his voice, Brian called out, “Dryden’s in town!”

I stopped mid-step, halfway up the staircase, causing a ripple of awkward shuffling as people tried to move around me. My heart skipped. For a Canadian and anyone familiar with hockey, the words “Dryden” and “goalie” could only mean one thing.

Ken Dryden. Six-time Stanley Cup champion with the Montreal Canadiens. The man who stood in net during the legendary eighth and final game of the 1972 Summit Series between Canada and the Soviet Union. A towering figure in the sport; not just for his physical presence, but for his intellect, poise, and the countless accolades that followed him.

Could it really be him?

The idea seemed absurd, yet tantalising. In that moment, the weight of our goalie crisis lifted just slightly, replaced by a flicker of hope and disbelief.

A Knock on the Door

The late afternoon light spilled across the park, casting long shadows over the wide green space at the heart of Cambridge. The River Cam meandered nearby.

I walked across the park; my eyes fixed on the row of terrace houses that lined its edge. I approached the address I was given. It was a centre terrace unit lining the side of the park, the kind of modest, brick-fronted home seen throughout towns and cities across the UK. Nothing flashy. No signs of grandeur. Just a quiet place tucked beside the park.

Considering Ken Dryden was one of the greatest and most successful ice hockey players of all time, it said a lot about the person. Rather than surrounding himself with trophies or reminders of past glories, he was helping his family settle into the rhythms of Cambridge life. School drop-offs, local shops, quiet walks. He was not trying to portray his success; he was trying to belong.

I stood at the door for a moment, taking in the simplicity of it all. I knocked.

When the door opened, Ken stood there tall and composed. He looked down at me with a curious smile, as if he already knew I wasn’t just a passerby.

“Can I help you?” he asked.

“Hello, Mr. Dryden,” I said, straightening my posture. “My name is Glenn Blaylock. I’m Captain of the Cambridge University Ice Hockey Team, and I’m looking for a goalie. Would you like to play?”

He paused, then replied with a hint of amusement, “Thank you for the offer, but I’m not a member of the university.”

“That won’t be a problem,” I said, smiling. “I have spoken to the university, and since you’re here writing a book, they’re willing to make you a Fellow. That would allow you to play.”

Ken Dryden smiled, the corners of his mouth lifting with a mix of admiration and disbelief.

“Very enterprising, Glenn. However, I don’t have my equipment with me.”

“We’re very resourceful,” I said. “We will have your gear shipped to Cambridge.”

Ken chuckled softly. He looked at me - did I really expect him to say yes to playing for a university team?

“What I will do,” he said, “is coach whoever you find to be your goalie.”

And just like that, the door didn’t close, it opened wider. Not to a player, but to a mentor.

And that, as I would come to learn, was even better.

We have a Goalie

The coach was parked beside King’s College Chapel. The hockey gear: sticks, skates, pads, helmets, and mismatched jerseys were stored below.

Players were settling into their seats, some with years of hockey behind them, laughing and swapping stories, eager for the game ahead. Others, who had not skated in years, were uneasy, wondering what they had signed up for.

But the most nervous of all was me.

We were just hours away from our season opener against the Nottingham Panthers. And our net? Empty. No goalie. No backup.

I have always believed in integrity, fairness, and honesty. But sometimes, when staring down disaster, even the most principled person might bend those values just a little.

As the coach pulled away from King’s Parade in Cambridge, I sat near the front, staring out the window. Then, partway through the journey, I stood up and walked down the aisle and sat beside Jeffrey.

Jeff looked at me, already suspicious. “Glenn,” he said, “I told you; I only put the pads on once. I’m not a goalie.”

I knew Jeff had grown up in Montreal during the golden years of the Canadiens’ dynasty. He had watched Ken Dryden stand tall between the pipes, intimidating opponents and inspiring generations. To Montrealers, the Canadiens were more than a hockey team, they were a legacy, a source of pride, and a living thread woven into the city’s identity and history.

So, I turned to him and said, “I understand you’re not a goalie. But just for a moment, I’d like you to consider, philosophically, if Ken Dryden, the legendary Montreal Canadiens netminder, were to be your personal goalie coach… what would your position be?”

Jeff’s eyes widened. He leaned back, stunned. “Well… if the greatest of all time was going to coach me, I’d have to play goal.”

“Fantastic,” I said, standing up quickly. “Ken Dryden is in Cambridge and has offered to be your coach. Congratulations on this amazing opportunity. The goalie equipment is in the coach.”

I didn’t wait for a reply. I walked briskly back to my seat, heart pounding, hoping the momentum would carry Jeff past the point of no return.

At any moment I expected to see Jeff walk towards the front of the coach, sit beside me, and say that he had changed his mind as the idea of him playing goalie in front of a team with imported players is the closest thing to a suicide mission he could think of. Honestly, I wouldn’t have blamed him.

But Jeff had mixed feelings. Just meeting Ken Dryden would be priceless, a brush with greatness, a moment to remember. But stepping into goal? That was something else entirely. He thought back to the one game he had played in net. His team had been dominant, keeping the puck in the offensive zone, controlling the pace. The action had barely touched his end, and he’d faced maybe four shots all game.

How much different could it be, he wondered.

When we arrived in Nottingham, I was still sitting alone, trying to imagine how the next two hours would unfold and whether a little trickery, backed by a legend, might just save our season.

Our Dunkirk Moment

We arrived at the arena with a mix of nerves and anticipation. In the changing room, Jeff called me over.

“Hey Glenn,” he said. “You probably don’t want to hear this right now, but the glove and blocker are for a right-handed player.”

I blinked. “That’s good to know,” I said, trying to process.

Jeff cleared his throat. “But I’m left-handed.”

I stared at him. I nodded slowly. “Sorry about that. Just do your best”.

What else could I say?

Jeff would play with the wrong-handed equipment until he flew to Canada for the Christmas break, returning in the new year with the proper gear.

The team stepped onto the ice to warm up. Jeff glided to the goal and motioned for the players to take shots. We took easy shots, as the team was well aware of Jeff’s experience playing goal. He was just beginning to get a feel for catching pucks with his glove hand and blocking with his left, when the whistle blew to start the game.

Jeff remembers what happened next. Instead of our team gaining control and pushing the puck toward the opposing goal, a Panthers player seized it, raced toward Jeff, fired a shot and scored. Jeff did not have time to react.

He took a deep breath to steady himself and thought, “Looks like this will be different from that intramural game.”

Then the shots kept coming. And coming.

With no home rink anywhere near Cambridge, every game we played was on the road. That meant few if any familiar faces in the crowd, no cheers from classmates or friends, just cold arenas and local fans supporting their home team.

I remember feeling oddly relieved that no one from Cambridge had been there to witness that game against Nottingham.

I never imagined a reporter from the Varsity; the university newspaper, would travel all the way to Nottingham to watch an ice hockey game. A few days later, the paper ran a piece about the game, highlighting how rusty and out of shape the players were, and naming Jeff, our goalie, the ‘Star’ of our team!

Massacre at Nottingham ice-rink

Cambridge University 0 Nottingham 20

By Christine Malpass

Cambridge University, who won the Varsity Match 5-1, met with disaster in the game on Sunday. They lost by 20 goals to nil to Nottingham, who are admittedly one of the strongest sides in the country. The team was made-up of experienced ice hockey players who were never-the-less extremely rusty. Almost all were Canadian although the English contingent of two players was the largest for years.

The game was by its very nature experimental and ironic though it now may seem in view of the score the star of the side was goaltender Jeff. Most of Nottingham’s goals resulted from errors in defence: indeed, the score might have been twice as many had it not been for his solid resistance. Cambridge’s best spell came in the second period of the match, when their players were getting a greater feel for the ice and their lack of fitness was not yet too evident. Nottingham scored six goals in the first period, four in the second and 10 in the third.

After the shock wore off, it was clear I had to say something.

I remember thinking about the British Army trapped on the beaches of Dunkirk, France, after being pushed back in the early months of the Second World War. With enemy forces closing in, the situation looked bleak. In response, Prime Minister Winston Churchill called on civilian boats to cross the English Channel and bring the soldiers home. Nearly a quarter of a million men were evacuated, allowing Britain to fight another day.

I sat down and wrote a letter to the editor. It was not defensive, and it was not an excuse, just a glimpse of what we were up against: no home rink, no regular training, and a team built more on heart than conditioning. I wanted people to understand that what they saw in Nottingham was not the whole story, it was the beginning of one.

To their credit, the Varsity published the letter.

Ice Shortage

By Glenn Blaylock

I could not fail to respond to the article headed ‘Massacre at Nottingham Ice-Rink’ in your edition of November 1st, which was a total misrepresentation of the circumstances.

To the uninformed eye the massacre was as much a defeat as Dunkirk in1940. Due to the lack of ice in the Cambridge area and the large expense of transporting a team almost 100 miles in search of the closest available rink, the university ice hockey team is usually limited to one or possibly two practices a year. In fact, due to the shortage of ice time in Britain, our team’s first time on the ice was during the game against one of the most seasoned teams in the country.

That night an effort was made to play every player equal time irrespective of talent. Some players had not skated for years let alone play the very demanding game of ice hockey. The lack of fitness was largely due to many of the players being unaware that weeks after arriving in Cambridge from abroad they would be battling it out on the ice.

After the next few games, the team will be selected, and we hope not only to redeem ourselves against the league's teams but also to repeat last year's victory over Oxford.

Ice hockey had stepped out of the margins of Cambridge life. Word had spread there was a team, and with it, the ritual of a varsity match. What had once been a quiet pursuit was now part of the university’s rhythm. But instead of added pressure, the attention brought encouragement. I began to hear it from students as they passed by, voices warm and sincere: “Good luck against Oxford!”

Empowered

Since Ken Dryden was not formally affiliated with the university, we looked for ways to introduce him to its culture and traditions. Denis Gauvreau, a PhD student, arranged a Formal dinner at Darwin College. We felt that Darwin, being a college for graduate students, would offer Ken a glimpse into life within the colleges.

Tradition marked the evening, with students and faculty dressed in black academic gowns. We settled into our seats at the long tables as the hum of conversation rose around us, Latin grace was murmured as candles flickered in silver candelabras. A multi-course meal was delivered by stewards who seemed part of the ritual itself.

It was a world steeped in ceremony and Ken blended in with ease. He asked thoughtful questions of the students seated nearby about their research, their aspirations, their impressions of Cambridge.

When we stepped out of Darwin College after dinner, Denis suggested we head to the Queen’s Head pub in Newton. The night had settled in, and a light rain misted the air. Elaine and I climbed into her car, while Denis, his partner Claire, and Ken followed behind in theirs. We navigated the narrow, winding roads until the pub emerged. By then, the rain had intensified. We parked quickly and dashed inside.

The pub was everything you would hope for in a rural hideaway: low ceilings, exposed dark wood beams, and a generous fire crackling in the hearth. We ordered bitters and stood at the bar, reflecting on the evening and the privilege of spending time with one of Canada’s most celebrated figures.

Partway through my pint, I noticed the others had not arrived. I turned to Elaine and said I’d go check. Stepping outside, I was met by a wall of rain. A single streetlamp cast a cone of light. Through the downpour, I saw the nose of a white car inch into the light. Then, fully illuminated, a tall figure came into view pushing the car from behind.

My heart sank. “What have we done?” I whispered. Ken Dryden, one of Canada’s most revered icons, was out there in the cold rain, pushing a car through the night.

I dashed out into the downpour, my shoes instantly soaked by puddles pooling in the uneven gravel. As I reached the car, I saw Ken, his jacket clinging to him, hair plastered to his forehead, still pushing with quiet determination. Denis was at the wheel, trying to get the engine to start.

“Ken!” I called out, half shouting over the roar of the rain. “Let me help!”

He looked up, gave a quick nod, and without a word, we leaned into the back of the car together near the pub’s entrance.

Inside, Elaine had already flagged down the bartender to help stoke the fire. We ushered Denis and the others in, dripping and breathless. The warmth hit us like a wave with the crackling fire and the scent of old wood.

We gathered around the hearth, steam rising from our clothes, and the mood shifted. The ordeal outside became a shared moment, humbling and oddly bonding. Ken, ever gracious, deflected attention from himself, asking about our impressions of the evening, the college, the students.

Denis leaned forward, eyes steady on Ken. “You’ve got the hardware, Ken. You’ve played alongside legends. If you had to choose one moment, that truly captures your career, what would it be?”

After a moment’s thought, Ken responded:

“I was playing hockey with Cornell, the team was circling through warmups, rifling shots my way. Stick, glove making routine saves. But then something shifted. In the blur of pucks and motion, I stopped thinking about technique. My body just knew. I could move whatever was closest, an elbow, a knee, a shoulder and the puck would find me. It was like I’d become the net itself, stretching into every corner. Liberating. For the first time, I wasn’t just guarding the goal, I was owning it. From that moment on, I felt empowered.”

Ken’s response would quietly shape the course of Denis’s life. It was more than a story, it became an enduring source of inspiration that Denis carried into boardrooms, classrooms, and conversations for decades to come.

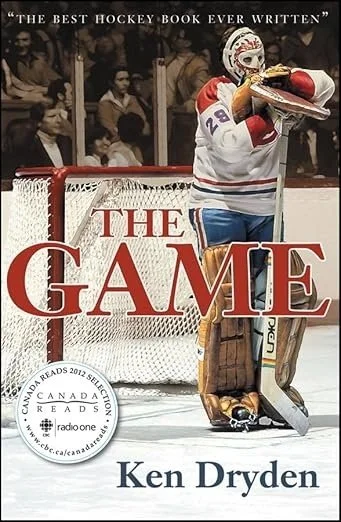

Much of Denis’s career would center on innovation. In his presentations, he often emphasised that feeling empowered is the key to unlocking creativity and meaningful change. To illustrate this, he would show a slide featuring an image of Ken Dryden making a save for the Montreal Canadiens, alongside the cover of Ken’s book The Game. Then he would share the story, how he had asked Ken what moment in his extraordinary career he cherished most. The answer, as Denis would later say, was “surprising, to say the least and completely unexpected.” It wasn’t the triumphs or recognition Ken remembered most, it was the feeling of being empowered.

As we left the pub, the rain finally let up. Ken and I pushed Denis’s car until the engine sputtered, then caught. Ken jogged alongside for a few steps before swinging himself into the passenger seat.

I stood there as they drove off, watching the taillights disappearing in the mist. The image of Ken pushing a car in the rain, uncomplaining, unnoticed, stayed with me. That quiet moment said more about his character than any trophy ever could. No spotlight. No fanfare. Just Ken.

Redemption – Almost

We had played another game and lost, but the team was beginning to find its rhythm. Our final match before the term break was against the Nottingham Panthers, the team that had delivered either our “Dunkirk moment” or a full-on massacre, depending on how you chose to remember it.

We were back in the same changing room where the Panthers had handed us our humbling defeat. But you would not know it from the energy in the air. The banter was lively, the mood upbeat as everyone felt better prepared this time. Then I looked up and smiled. Denis had walked in. He had missed the first game, but now he was here. And with him came something unspoken: belief that this game would be different.

Denis grew up in Quebec, developing his game on frozen ponds and in local arenas. He moved with ease on the ice, his stride smooth and his timing precise. A few seasons earlier, he had worn the captain’s ‘C’ for Cambridge, leading the varsity team to its first victory over Oxford in a long time.

We took to the ice, skating around our end of the rink and taking warm-up shots on Jeff. The stands were filled with fans, cheering for the Panthers. A few wives and girlfriends from our side sat near our bench, loyal and hopeful.

When Sean-Mun stepped onto the ice, he was stunned. “The rickety old stadium was packed with over 3,000 spectators, making a deafening noise. I’d never played in front of more than ten people before. But instead of nerves, I felt exhilarated. I learned from that moment, the bigger the crowd, the more I felt at ease.”

Nottingham - Cambridge University players wearing mismatched jerseys

The game started. Standing in front of our goal, Jeff could see how the flow of the play had changed. Denis, playing centre, quickly took possession of the puck and rushed into the Panthers’ end. The whole team looked energised and confident. Within minutes, Denis received a well-placed pass and scored.

For one hard-earned moment we led the game.

The Panthers responded with pressure, and a shot slipped past Jeff, tying the game.

Then Pekka, our Finnish forward, found the net.

Sean-Mun, who only played one season and scored once, still remembers what came next.

“A Panthers defenceman carried the puck into our zone. I lunged with my stick for a poke-check. The puck was mine. I turned, lit the afterburners, and flew down the right wing. The crowd surged. I cut hard toward the net, snapped a low shot to the far side.”

The buzzer blared.

I can still see Ian, skating full tilt the length of the ice, arms raised, shouting at the top of his lungs, “What a goal!”

Nottingham clawed one back before the whistle blew.

End of the first period: Cambridge 3, Nottingham 2. We were ahead. It felt surreal.

The second period began. Nottingham tied it early.

Then came the moment I’ll never forget.

One of their players crossed our blue line and unleashed a blistering slap-shot. The puck rose, fast and unforgiving. Jeff was square to it, perfectly positioned until it struck him in front of the neck. He dropped instantly, face down, motionless. Jeff had not been wearing a neck protector. Neither he nor I knew they had become standard equipment.

The arena fell silent. I was on the bench, but everything slowed.

Not surprisingly, we had no team doctor or medical staff. That just was not how things were done back then. So, I vaulted over the boards and skated to him, dropping to my knees.

“Jeff,” I said gently, “are you okay?”

A long pause. Then, quietly: “I think so.”

Every team should have a backup goalie. It’s standard, whether in hockey, football (soccer), or any sport where someone guards the net. The right thing to say would have been, “Take a break. Let the backup step in.” But we did not have one. So instead, I leaned forward and said,

“You do know we’re winning.”

Looking back, it probably was not the most empathetic thing to say, especially to someone who had come abroad to study law rather than play goal. In those days, though, getting knocked down meant getting up, shaking it off, and jumping back into the game. It was long before the lasting consequences of playing through injury were understood and fortunately Jeff would be okay.

Jeff stood, nodded, and returned to the crease. I was relieved, impressed, and more than a little guilty.

The game resumed. Martin, our British player, scored.

At the end of the second period, the score stood: Cambridge 4, Nottingham 3.

The change room buzzed with energy. We were on the cusp of something special.

As player-coach, it’s easy to lose track of the bench. Three players sat quietly. One of them motioned me over.

“Coach,” he said, “you promised everyone would get ice time before Christmas. We haven’t played yet.”

He was right. In the heat of the game, I had not given them the nod to take a shift. I looked at them, torn. We were having our best performance of the season, and they likely would not be on the team in the new year.

I hesitated, and thought to myself, “But we’re winning.”

The will to win can be intoxicating, whether you're a seasoned pro or a group of students striving to become competitive. But honouring your word is what truly matters, and what people remember. Not the scoreline. Not the stats.

The whole team took to the ice in the third period. We did not fully redeem ourselves. The final score was Panthers 6, Cambridge 4. But everyone played with heart, and it was the right thing to do.

Denis Gauvreau at near end of bench. Elaine wearing Half-Blue scarf behind him.

When Ken Came to Watch

Ken Dryden was eager to support Jeff in goal and wanted to see him play firsthand. With no home rink, we thought it best for Ken to travel to Nottingham for our first game after the term break. We played well in our previous match against Nottingham, and our final roster had been set.

Rather than having Ken ride with us on the coach, we felt it would be better if one of our players drove him. Tom Milroy volunteered. Soon after Ken had arrived in Cambridge, Tom saw him passing by and helped him settle into a place just down the road from where Tom lived. The two had struck up a friendship, often meeting at a nearby coffee shop or local pub.

On the day of the game, Tom arranged to drive Ken and three other players, including Jeff. It was a perfect opportunity for Ken to talk with Jeff about playing in goal. Tom drove to the meeting spot. Ken and Jeff were already there, but one of the players was late. They waited—and waited. Tom grew anxious. He knew the game could not start without our goalie.

Eventually, everyone arrived. Ken took the passenger seat beside Tom, while the other three squeezed into the back. Tom glanced at the time and realised they were behind schedule. If they were going to make it to Nottingham on time, he would have to push the pace. Normally, Tom was not one to drive fast, but this was different: they had 150 kilometers, over 90 miles, to cover.

He pressed down on the accelerator.

Ken and Jeff were deep in conversation about goaltending when Ken noticed the speed. He turned to Tom and asked, “Is this the normal speed limit?”

Tom replied, “No, but we’re late, and I’ve got to make up time.”

A few minutes later, he asked again, “Tom, are you sure we have to drive this fast?”

Tom did not hesitate. “We can’t be late for the game.”

I was waiting outside the arena, wondering where they were. The game was about to start, and I was starting to worry. It felt like déjà vu; once again, we were without a goalie.

Then the car pulled up, and they all piled out. I asked Ken how the drive had been. I do not recall his exact words, but one has stayed with me ever since: harrowing.

Thankfully, we had already brought Jeff’s goalie equipment, so he was able to suit up quickly and join us in time for the warm-up skate.

Ken made his way to the stands, took a seat, and retrieved a pad and pen, ready to observe Jeff’s performance in goal.

The game began. It might sound like an excuse, but we had not skated in weeks, and Nottingham was not about to take us lightly this time. Our performance was far from stellar. In fact, we played poorly. After being so eager to show Ken how much we had improved, I must admit—it was embarrassing.

As usual, our bright spot was Jeff in goal. He had upgraded his gear, now wearing a left-handed catching glove and a clear plastic throat guard hanging from his mask.

Near the end of the second period, I glanced up at the stands. Ken was leaning back in his seat, setting his pad down beside him.

I don’t even remember the score.

Paul Russell recalled, “after the game we all waited in the dressing room for Dryden to come in and give us his coaching advice, hanging our collective heads. The door opened and Dryden looked around the team and then at our goalie. ‘Jeff’, he said, ‘you need a new team skating in front of you.’

Paul continued. “I always thought that Ken Dryden handled that situation about as well as he could. There really wasn't much to say at that point and he was kind to Jeff and wasn't disrespectful of us by pretending that things were all OK. It was just another instance of his quality and class as a person”.

Watching Tom and Ken drive off, I remember the frustration of trying to compete without the chance to properly prepare. Still, I reminded myself: we had played better before, and we would again. The path forward was clear: refocus, regroup, ready us for the season’s most important match—Oxford, still two months away.

Plenty of time, I told myself. Or maybe I just hoped.

Stephen Beecroft, Ian Smith and Captain Glenn Blaylock

No Ice - No Problem

With no rink to train on, we had to improvise. With a roster of mostly Canadians, we turned to a national rite of passage, road hockey. We picked a time and claimed a spot; the parking lot behind the University Library on Sunday morning, when it was closed. All we needed were hockey gloves, sticks, tennis balls, and running shoes.

I tried to get the guys to focus on structure; passing drills, breakout plays, positioning, but the moment a stick hit pavement, it was like flipping a switch. Everyone was back in their childhood, reliving the hours spent on streets with friends, chasing the ball until it was too dark to play.

The team also needed conditioning, but everyone’s schedule pulled in different directions. So, we made a simple promise: from Monday to Thursday, every week during term, someone would be at Parkers Piece at 8 p.m., ready to run laps around the park. Each player committed to showing up at least two nights a week.

That first evening, I jogged over, unsure if anyone would show up. But as I reached the park, I saw most of the team already gathered beneath the streetlight at its center. The air was cool and damp, but thankfully dry. No one complained. We just started running.

Then, out of the quiet, a voice broke through: “Beat Oxford, Beat Oxford…” One by one, the team picked it up until the whole group was echoing it in unison. I smiled, not because it was loud, but because it was real. This was what determination sounded like.

The Perfect Arch

Our goalie Jeff and I were both at Queens’ College, and one day we noticed something curious. The Erasmus building had a series of arches at its base, and one of them happened to be almost exactly the width of a hockey goal. It was perfect!

Between lectures and seminars, Jeff would suit up with pads, gloves and stick and I would fire shots at him from every angle and height. It was not ice, but it was something. The arch became our makeshift net, and the sharp echo of an orange plastic ball striking brick rang through the quiet corners of college life.

The Erasmus building sits beside the President’s Garden, and one afternoon, someone must have heard us. A college porter appeared, stern-faced, and told us we could not play sports on college grounds. We tried to explain this was not just a game; we were preparing for the varsity match. But it did not matter. The rules were clear: rugby, cricket, and certainly not the “violent game” of ice hockey were permitted.

The location was too good to ignore. So, we put together a presentation outlining the challenges we faced preparing for the varsity match against Oxford and submitted it to the Board of Governors at Queens’ College. We were not optimistic; after all, we were asking to bend a rule that had likely stood for centuries.

Not long after, I was walking through the porters’ lodge when one of the porters called me over. He looked almost as surprised as I felt. “Apparently,” he said, “since you’re preparing for the varsity match, you’re allowed to use the arch for practice.”

After a moment of disbelief, I was elated. I jogged straight to Jeff’s room. We grabbed our gear, headed out, and soon the sound of shots ricocheting off brick once again echoed through the college grounds.

Every so often, effort, persistence, and a bit of luck align. This was one of those times.

Jeffrey Graham protecting the ‘Perfect Arch’ in Queens’ college.

Image by Sean-Mun Liang

Dryden’s Book

On the several occasions we spent time with Ken, our conversations often drifted toward stories from his hockey career and the sections of his book he was working on at the time. But they were not just tales of games played, or goals stopped. Ken spoke with a kind of quiet clarity. His stories were reflections, not recitations. He explored what it truly meant to be a professional athlete: the psychology, the responsibility, and weight of expectation.

I remember one conversation. He explained that the job of a goalie was not simply to stop pucks from entering the net. It was to give the rest of the team confidence; to be the steady presence they could trust. When players trusted their goalie, they could fully focus on pushing the play forward, scoring and winning.

Ken belonged to a generation that wrote in cursive, not keystrokes. One evening, he asked if I knew anyone who could help type his notes. I remembered that Kenny Williams, one of our teammates, had recently rented a typewriter. When I spoke to Kenny next, he said his wife, Anne, knew how to type and he was sure she would be pleased and honoured to help with Dryden’s manuscript.

Ken would bring Anne his handwritten drafts, asking her to keep them confidential. She would type them up and return both the originals and the typed copies.

Kenny had resisted reading the chapters. But one evening, unable to sleep, he gave in to temptation and read a part.

“It was a scene from the dressing room, just after Scottie Bowman had delivered a pep talk,” he recalled. “It was so funny I laughed out loud.”

Kenny has often thought of that moment.

“I was very likely only the second person to read a portion of what would later be considered one of the greatest sports books of all time; a remarkable confluence of circumstance and good fortune!”

We Need a Trophy

I met Ken at The Eagle, a student haunt I doubted he’d ever have wandered into on his own. We chatted about his book, how it was coming along, and soon the conversation turned to his career.

I said, “I’ve been part of many sporting events, as a player and as a spectator, where emotions ran high, win or lose. But I can’t imagine what it must feel like to win something as monumental as the Stanley Cup, especially in the final game of a seven-game series.”

Ken paused, thoughtful. Then he said, “The emotions are the same, whether you’re playing minor hockey, suiting up as a pro, or competing as a university student. What I felt when we won the Cup won’t be any different from what you will feel if you win your varsity match. If you do win, and you lift your trophy, that will be your Stanley Cup moment.”

For those unfamiliar with the world of ice hockey, the Stanley Cup is the trophy awarded to the champions of the National Hockey League, often referred to as the NHL.

The Stanley Cup was donated in 1892 by Sir Frederick Arthur Stanley, Lord Stanley of Preston, during his tenure as Governor General of Canada. He intended it for the “championship hockey club of the Dominion of Canada.” Years later, the fledgling NHL adopted the trophy, and ever since, it has been awarded to the winning team from either the United States or Canada.

After a gruelling playoff schedule, the NHL team that triumphs in the final best-of-seven series is presented with the Cup.

Tradition holds that the captain lifts it, gripping it with both hands due to its size, and hoists it overhead. With the trophy in hand, the team circles the rink to thunderous applause and cheers from the fans.

It’s a moment rich with emotion and joy, cherished by those who carry the Cup and by the adoring crowd that shares in their triumph.

Crosby 2009/Zuma/Alamy

Ken’s words echoed in my mind as I walked home. That’s when it hit me: we had a problem. There was no trophy. When Cambridge won the previous varsity match, I remember the anticlimax: no presentation, no skate around the rink, no hoisting anything overhead. Just a quiet win.

When I got home, I grabbed a sheet of paper and sketched a trophy and naturally, it resembled the Stanley Cup: a large rose bowl perched on a solid base. Then I wrote a letter to Joe Grigley, the Oxford captain, explaining that we needed a trophy. I enclosed the sketch and mailed it first thing the next morning.

Not long after, a letter arrived from Joe. “Looking forward to seeing the new trophy at the varsity match.”

We had no funds. So, we wrote a letter to the British Ice Hockey Association, recounting the long history of the Oxford–Cambridge Varsity match, and how the original trophy had been lost years earlier. We explained that a new trophy would help rekindle tradition and give the rivalry a symbol worthy of its legacy. We asked, humbly, if they might consider supporting its creation.

To my surprise, a letter arrived with a note saying they would contribute £100 toward a new trophy. In those days, that was no small sum. It felt like more than just financial support; it was a nod of recognition, a quiet affirmation that, in some small way, our efforts mattered.

The Other Team

Over the decades, Oxford had claimed the lion’s share of varsity match victories. Cambridge’s win the previous year was only its second in years, a rare bright spot in an otherwise lopsided rivalry.

Much of that imbalance could be traced to the Rhodes Scholarship program, which awarded generous funding to individuals who excel both academically and athletically. While the athletic requirement had softened over time, it was still very much in effect the year of our varsity match.

That year, Oxford fielded one of its strongest lineups in recent memory. Gary Lawrence, a Canadian forward, had captained the Yale University Ivy League team in the U.S. just the year before. Now, he was lighting up the U.K. sports pages, averaging two or more goals per game. Gary was second in the league in goals, even though his team, like ours, played only half the games. Without a home rink, they could not host visiting teams either.

Their captain, Joe Grigley brought his own impressive credentials: he had led the U.S. Deaf Olympic Team as captain, adding both skill and leadership to an already formidable squad.

“Light Blue Exodus for Varsity Match”

That was the headline splashed across the Varsity the day before we were set to play Oxford. I wondered if they were trying to make amends for the infamous “Massacre” article. Either way, it got the university buzzing about the match to come.

The piece noted that “six coach-loads of Light Blue supporters will be there to cheer Cambridge on.” Then came the familiar refrain: “Cambridge are underdogs again this year.”

I was not sure that last line was necessary; but maybe, in a way, it was better to be the underdog than to stride in with swagger, convinced victory was ours. There is something grounding about knowing you must earn your success.

On the team coach, the mood was sharp; players were focused, dialed in, but still loose enough for good chatter. Then, suddenly, silence. Ken Dryden stepped aboard.

He climbed the stairs slowly, offering quiet words of encouragement to each of us.

He wished everyone good luck, then walked down the aisle and stopped in front of Jeff. Without fanfare, he handed him a handwritten note, addressed personally, wishing him luck, signed simply: Ken Dryden. No speech, no spotlight. Just a quiet moment between the two.

Jeff still treasures that note. It was not just a gesture of encouragement; it was Ken Dryden showing up, fully present and genuinely caring about Jeff and his journey.

Years later, Sean-Mun captured in writing the feelings stirred by Dryden’s visit to the team.

“What struck me most was how human and compassionate Ken was toward us. Here was one of the best players in the world, giving his time to a ragtag university team. I’ll never forget him stepping onto the bus before we left for the Varsity Match in Streatham, wishing us luck. That alone felt like enough magic dust to carry us through.”

Ken stepped off. The doors closed. And with that, our convoy of coaches rolled toward London.

Personal note from Ken Dryden given to Jeff Graham.

Cambridge Poster for 1981 Varsity Match

The Assignment

Ice hockey is a physical sport. Players use their shoulders or hips to check opponents, often against the boards. The high speed of play in a confined space leads to collisions, falls, and constant battles for control of the puck. There are rules—checks such as hitting from behind or targeting the head are not allowed.

During the warm-up, I watched the Oxford players closely, paying special attention to Gary. He was tall, fast, and smooth with the puck. He was going to be a force, no question. We needed a plan.

I skated over to Steve. Throughout the season, his experience playing hockey in Canada had been evident; strong, physical, and skilled. He had the kind of grit we would need that day.

“Steve, we need to keep a close eye on Gary,” I said. “Wherever he lines up, I want you opposite him. If he’s on left wing, you take right. If he shifts to right wing, you go left. If he plays centre, you match him there.”

Then I laid it out clearly.

“Your job is to check him hard, but clean. Stay within the rules. We can’t afford penalties, especially if you’re off the ice.”

Steve smiled, calm and confident. “No problem, coach.”

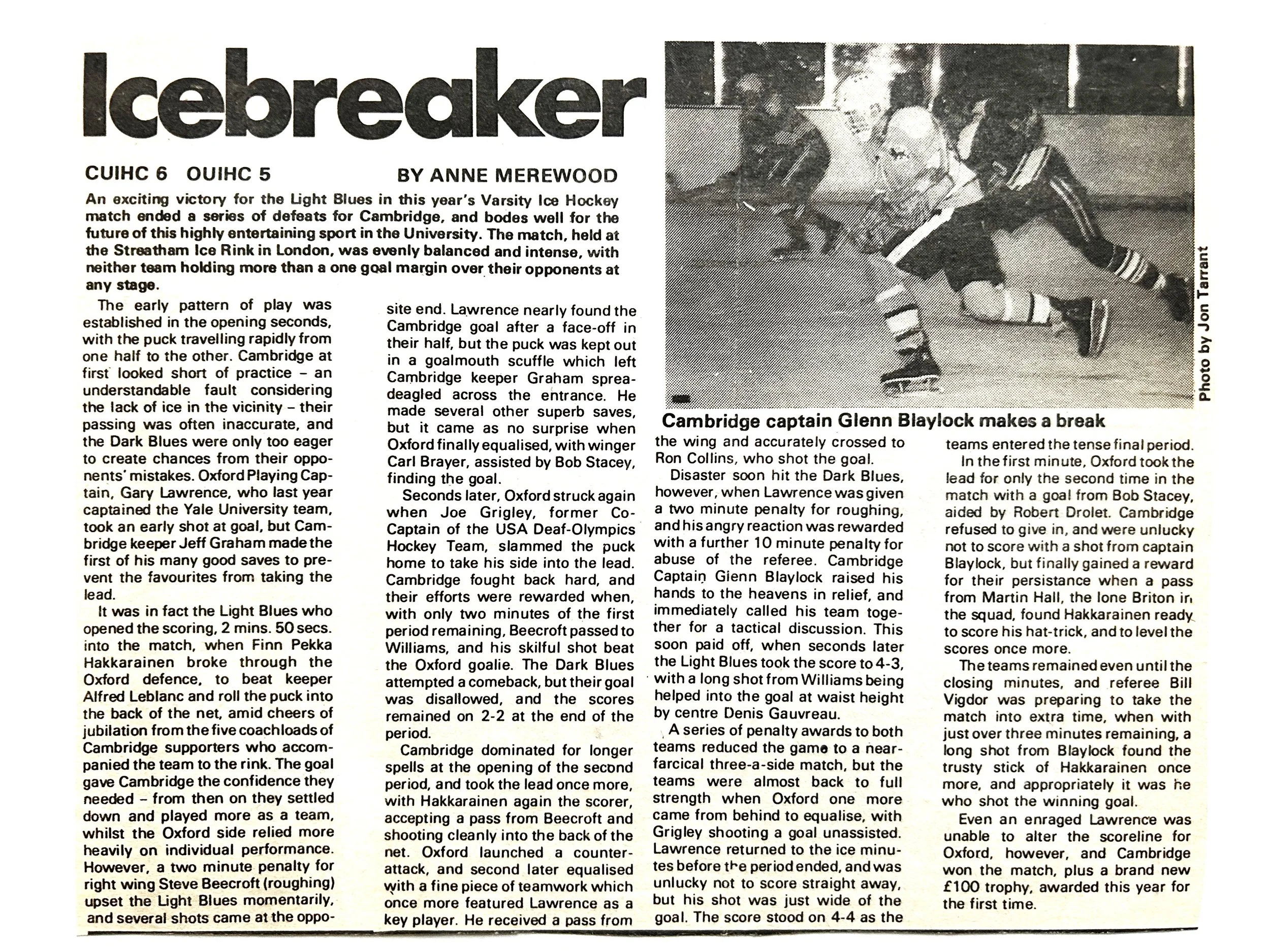

Varsity Match – 1981

The atmosphere was electric; supporters of both teams packed the arena, voices loud, eyes fixed on the ice, eager for the match to begin.

Between the benches sat the new trophy, placed carefully on a table. It looked just as I had sketched it - almost. One thoughtful addition had been made: two silver rings were affixed to either side of the rose bowl. From each ring hung two ribbons, one dark blue for Oxford, the other light blue for Cambridge.

Bob Pimm, who had played goalie in the previous varsity season, joined us behind the bench to help coach. Having him behind the bench was a real asset. By handling line changes, he allowed me to focus on the game.

The teams lined up for the first face off. The puck dropped and the play started.

You could tell our team had not been on the ice for a while. Our passes were inaccurate, and Oxford took advantage. Gary intercepted a pass, raced towards the net and let loose a shot.

A reporter from the Varsity later wrote, “The Cambridge keeper, Jeff made the first of many good saves to prevent the favourites from taking the lead.”

We quickly recovered and started to hit our stride. Within the first three minutes of the game, Pekka broke through their defense and rolled the puck behind their goalie!

Cambridge 1 – Oxford 0.

The teams lined up again. Gary positioned himself on the left wing. Steve from our team faced him. The puck dropped and was shot towards the boards. Gary skated to collect the puck but was checked hard into the boards by Steve. The referee blew his whistle and pointed toward the penalty box for Steve to sit for two long minutes.

We were one player short.

“Gary nearly found the Cambridge goal, but the puck was kept out in a goalmouth scuffle which left Cambridge keeper spreadeagled across the entrance.” reported the Varsity.

Jeffrey Graham protecting Cambridge goal.

Shortly after, with some clean passing by Oxford, Joe, the former captain of the USA Deaf Olympic team, scored again.

I could not help saying to myself: “So much for our great plan.”

The game continued with end-to-end action. Steve, back on the ice, passed to Kenny whose “skillful shot beat the Oxford goalie.” The game was tied 2-2 at the end of the first period.

The second period started with a flurry. Pekka scored again and Gary responded with a perfect pass to one of the Oxford players who slipped the puck behind Jeff.

Steve continued to check Gary hard but this time within the rules. Gary retaliated and was given a 2-minute penalty for roughing. He challenged the call with the referee who then gave him a 10-minute penalty for “abuse of the referee.”

The Varsity later reported:

“The Cambridge captain raised his hands to the heavens in relief and immediately called his team together for a tactical discussion. This soon paid off, when seconds later the Light Blues took the score to 4-3 with a long shot from Williams being helped into the goal at waist height by Centre Denis Gauvreau.”

“Looks like our plan was working after all,” I thought.

Players collided, shoving Jeff away from our goal. An Oxford forward, stationed in front of the net, took a pass and fired the puck. For a moment I feared the worse until I saw Brian Omotani, one of our defencemen, standing in a goalie’s stance between the posts. The puck hit him squarely in the chest and fell to the ice. Brian gathered it, made a pass, and the play surged back toward the Oxford end.

Gary returned to the ice. Joe scored an unassisted goal, and the teams were tied 4-4 at the end of the second period.

The third period started, and Oxford quickly scored. We pushed hard and Martin, our British player, passed to Pekka who scored his hat-trick to equalise the score at 5 to 5.

The play continued end to end. With less than three minutes left in the game, I can still remember this clearly as if it happened yesterday. I was playing left defence and took a shot from just inside their blue line. I saw the puck rise and the Oxford goalie moving across the crease to make an easy save. What seemed like slow motion, I saw Pekka raise his stick and tip the puck with the blade of his stick. The puck changed direction and went into the net.

Cambridge 6 – Oxford 5.

Pekka threw both arms high in celebration, so high he nearly toppled backward. Martin, standing nearby, reached out instinctively and caught him before he fell. Pekka still recalls that moment with pride. “Its was one of the best moments of my sports career,” he says, the memory as vivid now as it was then.

Oxford attacked us with vengeance.

I watched Jeff, making saves that Ken Dryden would be proud of. I could not help thinking of the hours we spent taking shots by the arch under the Erasmus Building at Queens’ college.

The whistle blew to finish the match.

We won.

Pekka Hakkarainen celebrates his winning goal.

Our ‘Stanley Cup Moment’

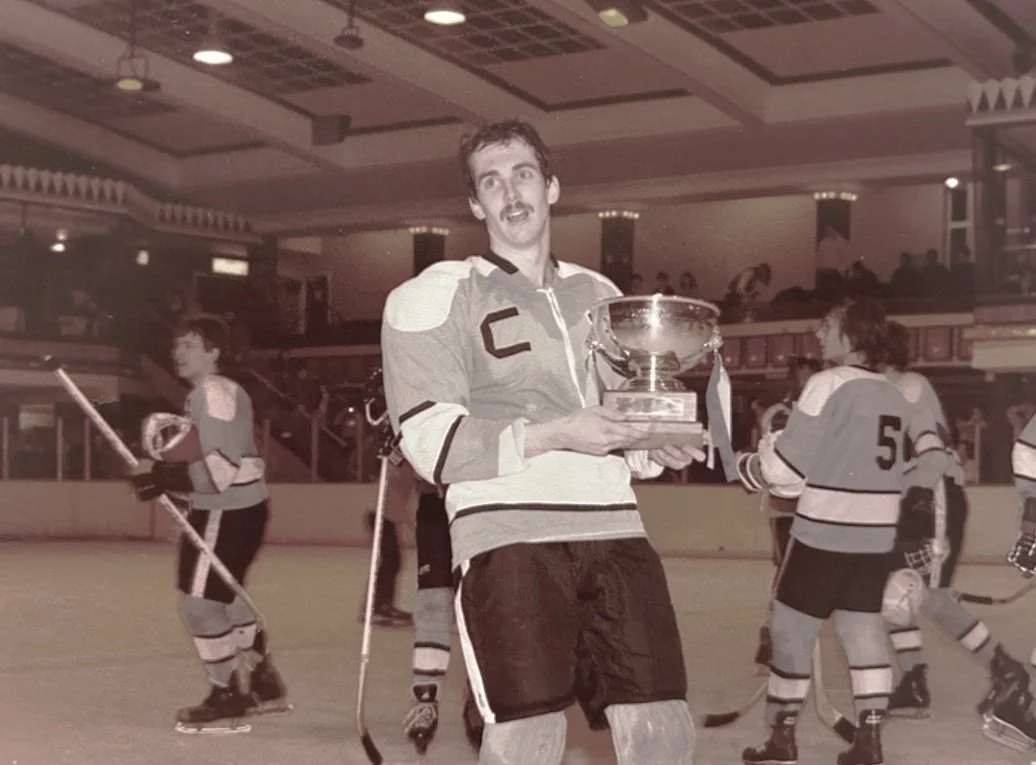

After we shook hands with the Oxford players, we lined up for the award presentation. A representative from the British Ice Hockey Association walked onto the ice, lifted the trophy, and handed it to me. I raised it high, and the whole team skated our victory lap. The crowd cheered as we passed by, the smiles on our faces radiant.

It was not that we were highly skilled athletes or that we had bested an elite team. It was that we had persevered through what, at times, felt like insurmountable hurdles.

We circled the rink, and I offered a silent thank you to Ken for the conversation that helped shape this moment. Ken was right: I could not have felt more elated or relieved.

Our ‘Stanley Cup Moment’ raising the new varsity trophy high (left of image).

Year-End Dinner and ‘A tree falls in the forest.’

It’s customary to hold a formal dinner to celebrate the season and the varsity match. Ours was held at Sidney Sussex College, nestled in the heart of Cambridge. Black tie tuxedos, or outfits resembling them, were worn. The evening was a chance to mark our victory and honour the players who had stood out during the match and throughout the season.

What made the evening truly special was the presence of Ken Dryden as our guest of honour. He made a heartfelt and humorous speech.

He joked that in all his years of playing hockey, he had never heard of anyone, especially a key player, missing a game because they were performing in a musical. Steve laughed the loudest, knowing the joke was on him.

Ken congratulated the team on winning the varsity match, though with a hint of surprise. He recalled the game in Nottingham where, after losing count of shots on goal, he had concluded, in his words, “It wasn’t the goalie that needed help.”

Ian, our team treasurer, had the unenviable task of reviewing the club’s finances. We had a good laugh when he suggested that two players were “wasting their time at Cambridge and would be much better off as car salesmen on commission” as they had convinced a couple dozen students to attend the Varsity Match and buy team t-shirts as well.

Before sitting down, Ian referenced Ken Dryden’s earlier remark, saying, “Our team was much more than just a hockey team.”

Ian recalls that, “Ken came up to me after the dinner and thanked me for my comments, saying that our team spirit and the shared values and jokes have been great to see in the context of such a famous and non-Canadian place.”

As Ian reflected, “Perhaps Ken understood this before many of us did.”

Over the years, I have often wondered why Ken took such an interest in us. Our hockey skills were, frankly, modest at best, especially compared to the Ivy League teams he had known in his youth.

Reading what Ian shared, I finally understood: Ken was struck by the fact that a hockey club could survive and even thrive for so many years in a place where it had no business existing. We did not even have a rink. And we did not take ourselves seriously as hockey players as we all knew that was not why we were there. And yet, somehow, what we built meant more than we realised. Not because of the level of play, but because of the spirit behind it; the camaraderie, the persistence, the improbable joy of keeping the game alive where it was not supposed to be.

When the awards were announced after the dinner, Ken was gracious. He offered handshakes to each recipient and stood patiently while our photographer took pictures, as if to quietly honour the moment and preserve it for all time.

It was no surprise that Pekka was voted Most Valuable Player of the varsity match, having scored four goals.

Ken shook Pekka’s hand firmly and presented him with an official pin from the Montreal Canadiens; the team where he won six Stanley Cups. Pekka remembers the moment clearly. He held onto that pin for years as a quiet reminder of the night a legend took the time to honour his effort.

The photographer was one of our own, a teammate. He owned a high-quality camera with a large lens, capable of capturing sharp, professional-grade photos. I thanked him for stepping into that role, realising we had no pictures with Ken. Fortunately, that night many were taken with the team and our honoured guest.

The next morning, I was walking along the alleyway behind Queens’ College when I saw our photographer. I smiled, still thinking about the evening and excited to see the photos. But I noticed a forlorn look on his face.

He hesitated, then said quietly, “There’s been a disaster.”

I could not imagine what could possibly go wrong after everything we had been through.

“I forgot to put film in the camera,” he said.

I stared at him, stunned.

This was long before everyone carried a smartphone capable of taking photos. Capturing selfies, especially with famous people, would not become common practice for many years.

“I’m truly sorry,” he said.

Later, I thought of the saying, “If a tree falls in the forest and no one is there to hear it, did it really happen?”

We had no pictures. No record of our time with Ken Dryden. No proof. It was as if it had never happened.

I said quietly, “Someday, I will have to write this story.”

After the Match

Joe Grigley, the captain of the Oxford team sent me a letter that ended as follows: “It was a great match, and will remember it forever. Thank you so much for the competition and the help. Yours Ever, Joe”

Elaine and I married in Cambridge that summer. Ian and his wife were our witnesses at a civil wedding in the Registry Office. We moved to Canada that year.

Jeff Graham never played in goal again. He became a successful lawyer in Toronto, Ontario.

With Gary Lawrence at the helm, Oxford would win the varsity match the next year.

Cambridge soon began holding regular on-ice practices at the new rink in Peterborough, just an hour’s drive away.

Sean-Mun Liang captained the Cambridge team in 1982–83, leading them to first place in the English league second division and a tie against Oxford; the first tie since 1930.

Ken Dryden’s book, ‘The Game’ was published in 1983. To this day it is considered one the greatest pieces of literature about ice hockey.

Year 2018 - St. Moritz, Switzerland

The 100th varsity match was set to be played in the evening. One of the original varsity trophies had been rediscovered and was now presented to the winner. Still, I’d often wondered what became of the trophy we had created; the one passed between the varsity teams for many seasons.

Prior to the varsity match, Oxford’s Vikings would face off against the Cambridge Narwhals. Both teams were largely composed of talented players who did not qualify for the varsity squads. Their matches are now highly competitive.

It was midday and the game between the Vikings and the Narwhals would be starting soon. I wandered over to the change rooms to soak in the pre-game energy. And there it was. Our trophy was sitting on a table near the doorway of one of the dressing rooms. I must have looked surprised. What was it doing here?

A player walked up, and I asked if he knew what the trophy was for. His face lit up.

“This is the trophy we play for every year,” he said proudly. “It’s been sitting on my mantel above the fireplace in Cambridge for the past three years. We’re hoping to make it four.”

I asked if he knew where the trophy came from.

“Sadly, no,” he replied. “It’s become such an important part of the rivalry, but no one seems to know its origin.”

“Well,” I said, “let me tell you where it came from and the role one of Canada’s greatest hockey players had in its creation.”

He was thrilled. Then he insisted: I should be the one to present the trophy after the match.

When the game ended, I was ushered onto the ice. I expected to shake the captain’s hand and hand over the trophy quietly. Instead, someone handed me a microphone and asked me to explain why I was making the presentation.

So, I told the story, how a conversation with Ken Dryden had sparked the idea, how we modeled the trophy after the Stanley Cup, and how it became a symbol of effort, pride, and shared legacy.

I then handed the trophy to the captain of the Cambridge team.

Jeff Graham and Glenn Blaylock with 1981 trophy

Calum Nicholson with the mountains of St. Moritz.

Jeff Graham, Sean-Mun Liang and Glenn Blaylock

Gary Lawrence - Still a formidable opponent.

Year 2020 - Full Circle

Life, with all its twists and turns, has a way of surprising you.

I had been retired for several years when, one day in early March, I opened my laptop and saw an email from my oldest son, Jeffrey. Yes, he is named after Jeff, who was our goalie the year I captained the varsity team; a friendship that has lasted ever since.

My son had gone to Cambridge to pursue a graduate degree and joined the ice hockey team. He had spent years playing hockey in Canada: tall, strong, fast, with a slapshot from the point that could rattle the boards.

That year, Cambridge opened its new ice rink. Players cycled to weekly practices, and when the varsity match came around, the score told the story: Cambridge 8, Oxford 0.

I opened Jeff’s email and clicked on the attached video. The Vikings and Narwhals had just finished their match.

Jeff stepped onto the ice. Over the sound system, a voice announced: “Jeff is presenting the trophy, as his father had it made many years ago.”

Jeff shared the story behind the trophy’s origins, then stepped forward to present it to the captain of the Cambridge team.

I felt a lump rise in my throat. Watching him present the trophy, I could not help but think back to those moments: Ken Dryden pushing the car through the rain, climbing aboard our bus and handing our goalie a personal note of good luck. He offered his time, his wisdom, and a quiet kind of magic to a group of lads doing the best they could in the face of countless challenges.

To this day, I truly believe that, for a moment in our lives, we were touched by greatness.

Dedication

A few weeks after graduating, Kenny was walking along a quiet King’s Parade with just a few tourists strolling by and the occasional student hurrying past on errands.

He noticed Ken Dryden sitting alone on a bench, his posture relaxed, eyes thoughtful. Kenny walked over and sat down beside him. They chatted for a while about the typing of his notes, and other things.

“It wasn’t so much what he said that stayed with me,” Kenny would later reflect, “but the way he was: curious, present, and fully attuned to everything around him.”

We dedicate this story to Ken Dryden. Though our time together was short, it meant more than words can say.

Ken Dryden, 1984 Olympics, Sarejevo

Image by Everett/Alamy

More Memories

A Silent Nod

The third period of the 1981 varsity match was about to begin. Paul Russell sat on the bench with his line-mates, eager for their turn to go over the boards. When the whistle blew, it was their moment. Paul started to rise but felt a firm hand on his shoulder.

He turned and saw Bob Pimm, last year’s goalie, now helping coach from behind the bench. Bob’s eyes were steady, his hand resting on Paul’s shoulder pad. He gave a slight nod. Paul nodded back. He understood.

Paul stayed seated and smiled. It was the right call. With the game tied and the third period underway, the team had to commit fully to whatever gave them the best chance. Paul knew he was one of the slower players, and in that moment, stepping aside was the best thing he could do for the team.

When the final whistle blew and Cambridge won, Paul joined the team as they circled the rink with the new trophy.

Paul also knew the reason he could not play as well as he knew he could: his left knee had been unstable and painful all season.

When he returned to Canada, an orthopaedic surgeon confirmed what Paul had long suspected, a torn cartilage and a torn anterior ligament in his left knee. When he heard the diagnosis, he simply said, “No wonder it hurt so much.”

“But I was so desperate to play on the Blues team,” Paul recalls, “it did not matter to me… Slow, lame or not—I enjoyed it all.”

Pekka in Boston

Pekka Hakkarainen would go on to study for his PhD at MIT. One day, he visited Customs in Boston to collect his skates, which had been shipped to him. As he approached the counter, the Customs official looked up, noticed the Montreal Canadiens pin on Pekka’s jacket, and said, with a stern expression, “You can’t come in here wearing that.” Taken aback, Pekka replied, “This pin was given to me personally by Ken Dryden.” The officer paused, then offered a quiet nod of respect before handing Pekka his skates.

Denis campaigns for a seat in Parliament

Denis Gauvreau and Ken Dryden stayed in touch for 45 years, reconnecting in Toronto from time to time. In 2008, Denis began considering a run in the upcoming federal election. He travelled to Ottawa to meet with various individuals and assess whether to pursue a seat in Parliament. Among them was Ken, who had served as a Member of Parliament since 2004.

They sat together in Ken’s office for an hour. Ken spoke candidly about the realities of political life, offering advice Denis remembers as “very practical,” not about grand strategy, but about the daily grind of campaigning, the discipline it demanded, and the resilience it required.

Denis entered the race polling third. It was a hard-fought campaign, and for Denis, an eye-opening experience into how the political process truly worked. On election night, he finished second. Ken was re-elected, having endured his own exhausting campaign.

The next morning, Denis was at home when the phone rang. It was Ken. Denis recalls, “He asked what my thoughts were about the experience of campaigning and how I was feeling.”

Denis has always remembered that call. Ken had taken the time to reach out; not as a politician, but as a friend. It was a quiet gesture of respect, a recognition of effort, and a reaffirmation of the friendship they had built since their days together in Cambridge.

It was the only call Denis would receive that day.

Let’s Play Golf

Years later, Tom Milroy moved to Toronto. One morning, while walking his daughter to school, he spotted Ken Dryden, who happened to live nearby. They would often run into each other, share a quick conversation, and continue with their day.

One afternoon, Ken said, “Tom, let’s play golf together sometime.”

Tom smiled. “Great. Should be fun.”

“I’ll drive,” Ken added.

Tom paused, surprised. “Ken, that trip to Nottingham was years ago!”

Ken just smiled.

When they finally arranged to play - Ken drove.

Gary Lawrence of Oxford Remembers

“My recollection is that I was continuously swarmed by the Light Blues (not only Steve) and the referees had not understood interference to be a penalty.” That was Gary Lawrence’s response after I sent him the draft of the section where I had assigned Steve Beecroft to check him close, but clean.

Thinking back, while it was Steve’s primary task to contain Gary, the rest of us took our chances too. We were all checking him whenever the opportunity arose.

Gary also recalled, “I had invited a young woman to the game to impress her, but my ten-minute misconduct penalty was hard to explain.”

“Sorry about that,” I thought while reading his reflection. Still, we scored while Gary was off the ice and took the lead.

Though not directly tied to our story, Gary shared a meaningful coincidence: “I had the pleasure of sitting on a concussion protection board with Ken Dryden. We were also connected through McGill. Dryden was a great Canadian and has left us with a tremendous legacy.”

Hockey Hall of Fame, Toronto, Canada

On August 19, 1998, a ceremony was held at the Hockey Hall of Fame to celebrate a new display depicting the oldest rivalry in the history of ice hockey: the Oxford versus Cambridge university teams. The first game was played on an outdoor rink in 1885 in St. Moritz, Switzerland, and the tradition continues to this day.

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the players who shared their reflections on these events and their personal stories involving Ken Dryden, namely Steve Beecroft, Denis Gauvreau, Pekka Hakkarainen, Sean-Mun Liang, Tom Milroy, Brian Omotani, Paul Russell, Bill Scott, Ian Smith, Ken (Kenny) Williams and Gary Lawrence.